|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 29(4); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the adoption and utilization of personal health records (PHR) across Korean medical institutions using data from the 2020 National Health and Medical Informatization Survey.

Methods

Spearheaded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and prominent academic societies, this study surveyed PHR utilization in 574 medical institutions.

Results

Among these institutions, 84.9% (487 hospitals) maintained medical portals. However, just 14.1% (81 hospitals) had web-based or mobile PHRs, with 66.7% (28 of 42) of tertiary care hospitals adopting them. Tertiary hospitals led in PHR services: 87.8% offered certification issuance, 51.2% provided educational information, 63.4% supported online payment, and 95.1% managed appointment reservations. In contrast, general and smaller hospitals had lower rates. Online medical information viewing was prominent in tertiary hospitals (64.3%). Most patients accessed test results via PHRs, but other data types were less frequent, and only a few allowed downloads. Despite the widespread access to medical data through PHRs, integration with wearables and biometric data transfers to electronic medical records remained low, with limited plans for expansion in the coming three years.

The fusion of healthcare and information technology (IT) has ushered in pivotal changes in the modern medical realm. This integration de-centralized the traditional authority of physicians and enhanced patient involvement and self-management capabilities [1]. Moreover, the incorporation of IT spurred the development and dissemination of new medical services and solutions. Amid these transformative shifts, personal health records (PHRs) have emerged as a key tool among various strategies to integrate IT into healthcare, offering tangible benefits to patients. Beyond providing a platform for patients to generate and manage their health information, PHRs encompass a range of convenient features, from accessing medical records to facilitating hospital appointments and billing services. Furthermore, PHRs play a crucial role in expanding the quality and scope of medical services by offering patients access to remote medical services and IT-centric medical initiatives such as virtual clinical trials [2,3].

The utilization of PHRs in healthcare varies substantially, influenced by factors such as national medical cultures, infrastructural differences, and policy frameworks. In contexts where patient autonomy is integral to medical decisionmaking, systems have been developed to empower individuals with PHRs, enabling them to manage their health proactively. The United States established a foundation for PHR adoption through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act and electronic medical record (EMR) incentive programs. Collaborative efforts in 2010 between the US Department of Veterans Affairs and multiple institutions led to the launch of the “Blue Button” service, which initially targeted veterans. This service, which expanded to all patients by 2013, began by facilitating the exchange of patient information in PDF format [4]. However, it has evolved to support inter-institutional PHR data transfers and integration with third-party applications, thus promoting ongoing personal health data utilization. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service app allows citizens to access their medical records [5]. Simultaneously, it offers basic medical services such as symptom input, outpatient appointments, and repeat prescription orders. Finland centralized its citizens’ medical records using the Kanta system, allowing data utilization without national reimbursement [6]. Meanwhile, the Netherlands, through the MedMij project, champions the use of wearable devices by third-party vendors for PHRs [7]. Conversely, South Korea primarily adheres to a hospital-linked PHR blueprint. It is worth noting the absence of comprehensive research into the functional deployment of PHRs, especially in crucial domains like medical data interchange and its relay to third-party entities.

This study explored the PHR landscape in Korea using data from the 2020 National Health and Medical Informatization Survey [8]. Through a meticulous assessment of PHRs’ cardinal attributes in practice, we aim to provide stakeholders with robust data to steer dialogues on PHR evolution and its prospective integration into the country’s healthcare system. Our insights are expected to guide and optimize the forthcoming initiatives of Korean PHR firms, health establishments, and the patient community.

In 2020, an IT survey was conducted under the auspices of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korea Health Information Service. This initiative was jointly carried out with related academic societies such as the Korean Society of Medical Informatics, the Korean Information Technology of Hospital Association, and the Korean Health Information Managers Association. While this survey was built upon the foundation of previous surveys from 2015 and 2017, it was designed to cover a broader range of topics, including the standardization and security of medical data, the integration of various systems and data, the use of secondary data, personnel, and IT system governance. A total of 94 questions were crafted to address four domains, with one domain specifically focused on assessing the “advanced healthcare IT system status” including PHRs. A detailed analysis of this report has been presented in previous paper [9].

Given that the survey targeted hospitals across the country with varied sizes and infrastructures, the scope of the PHR investigation was balanced in line with other domains. In this survey, the term “PHR” denotes an information system designed for the electronic recording of an individual’s health-related data. This encompasses technologies and services where an individual proactively integrates and manages their medical information, lifestyle habits, genomic data, and public health information. Furthermore, individuals can selectively share and utilize this information as they deem appropriate. For this survey, a PHR was defined as a web or app system implemented by a healthcare institution to provide patients with convenient functionalities and medical information. The questions within the PHR domain were categorized into the following: the adoption and planning status of the information system, online features for patient convenience, current operation status and future plans of the PHR system, the extent of hospital data provision, and the authentication methods used in the PHR system.

Domestic medical institutions are classified based on bed capacity: tertiary care hospitals handling intractable diseases with more than 100 beds, general hospitals with fewer than 100 beds, and hospitals with a capacity ranging between 30 and 100 beds. The survey items related to PHR were conducted across all 574 medical institutions without distinction of type or bed count. However, hospitals with a capacity between 30 and 100 beds were partially sampled. This study utilized multiple survey methods, including face-to-face interviews, online surveys, and surveys via fax/email. The detailed design and methodology of the survey have been reported in previous research [9]. This study was exempt from ethical review and approved (IRB no. 2021-0622).

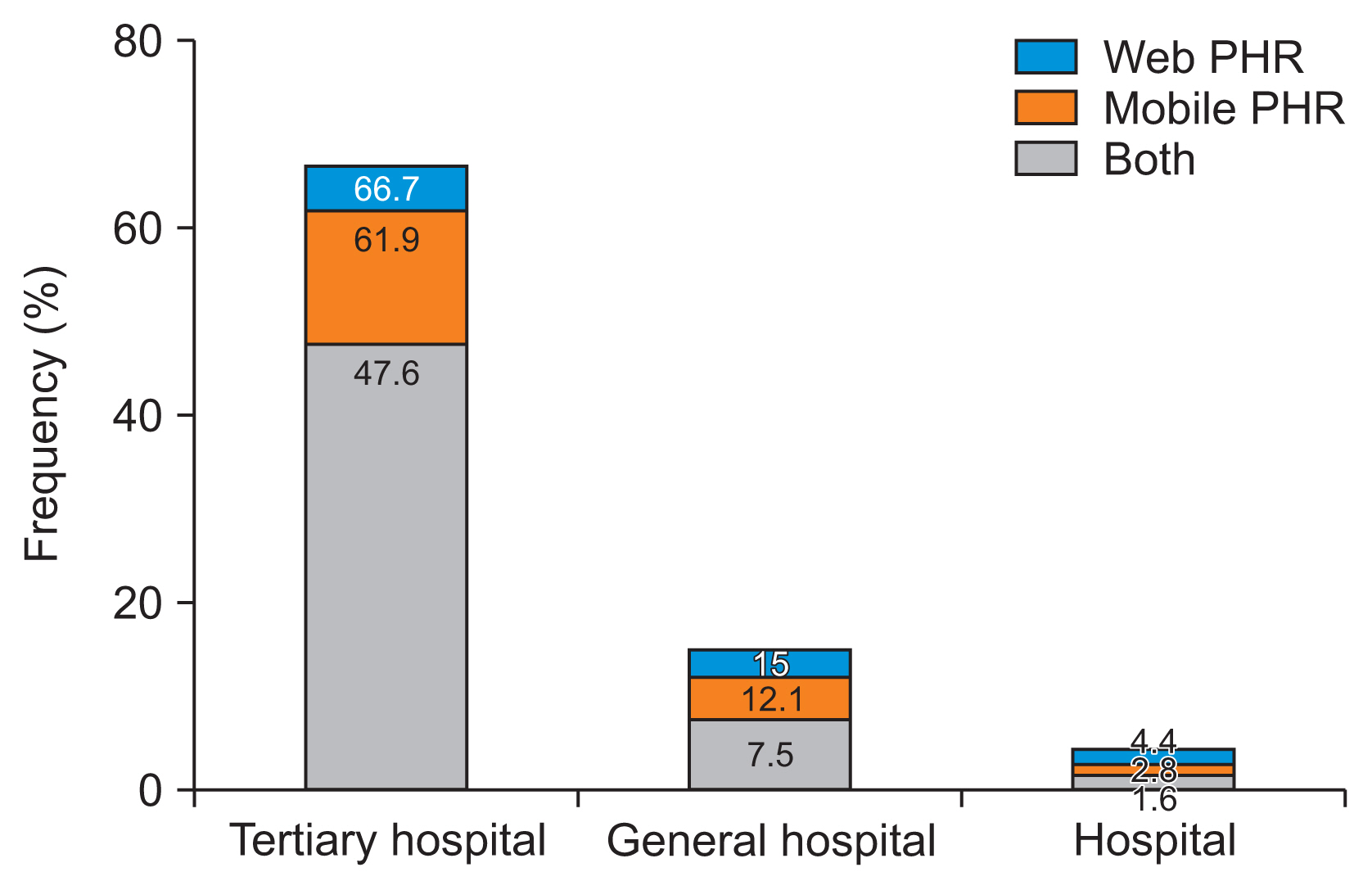

We examined the adoption status and types of PHRs across various medical institutions. In light of the recent trend of medical facilities providing patient information through multiple channels, we carried out a survey specifically assessing standard medical institution portals, web-based tethered PHRs, and mobile PHRs. Among the institutions surveyed, 487 hospitals (84.9%) had set up a medical institution portal. However, only 81 hospitals (14.1%) had introduced web-based or mobile PHRs. Focusing on tertiary care hospitals, 28 out of 42 (66.7%) operated either web or mobile PHRs. For general hospitals, 42 (or 15.0%) had PHRs, while only 11 smaller-scale hospitals (4.4%) had them in operation (Figure 1). There was a noticeable trend for larger hospitals to make more extensive use of PHRs. Moreover, many of the hospitals that had not yet adopted PHRs displayed a high inclination to implement them within the next 3 years.

A characteristic of tethered PHRs is their ability to offer patients access to medical information and various service functionalities. We investigated which services each hospital’s PHR provided. Services offered either through web or mobile platforms included the application and issuance of certification documents, provision of educational information, receipt of medical fees, and appointment reservation features (Table 1). For the online application and issuance of certification features, tertiary care hospitals had the highest adoption rate (87.8%). General hospitals and smaller hospitals registered considerably lower rates (19.7% and 7.9%, respectively). Additionally, when it came to the online provision of educational information, tertiary care hospitals again led, with an adoption rate of 51.2%. In comparison, general hospitals with more than 300 beds and smaller hospitals showed relatively lower adoption rates (10.2% and 7.1%, respectively). Regarding the feature of online payment receipt, tertiary care hospitals once again dominated with an adoption rate of 63.4%, while general hospitals and smaller hospitals had lower rates (12.8% and 4.4%, respectively). For the online appointment reservation feature, tertiary care hospitals likewise reported a very high adoption rate (95.1%). General hospitals and smaller hospitals had adoption rates of 46% and 17.5%, respectively.

Tertiary hospitals had the highest proportion of institutions with PHRs allowing patients to view medical information online via mobile devices (64.3%). Meanwhile, general hospitals with more than 300 beds, general hospitals with fewer than 300 beds, and smaller hospitals exhibited usage rates of 22.6%, 2.5%, and 0.9% respectively. Among healthcare institutions that had not implemented the online medical information viewing feature, the intent to introduce this capability within the next 3 years was indicated by 11.9% of tertiary care hospitals, 14.3% of general hospitals with over 300 beds, 22.5% of those with fewer than 300 beds, and 14.6% of smaller hospitals. Moreover, the implementation of features such as the ability for patients to download medical information online, transfer medical information online, and input their own data directly were generally found to be lacking. Among institutions that had not incorporated the ability to download medical information, plans to introduce this feature within the next 3 years were indicated by 28.6% of tertiary care hospitals, 13.5% of general hospitals with more than 300 beds, 22.5% of those with fewer than 300 beds, and 15.1% of smaller hospitals. For the feature enabling the transfer of medical information online, the percentages were 19% for tertiary care hospitals, 12% for general hospitals with more than 300 beds, 20% for those with fewer than 300 beds, and 13.8% for smaller hospitals. Additionally, among institutions that had not incorporated the patient’s direct input feature, the intent to implement within the next 3 years was expressed by 16.7% of tertiary care hospitals, 16% of general hospitals with over 300 beds, 19.1% of those with fewer than 300 beds, and 13.4% of smaller hospitals.

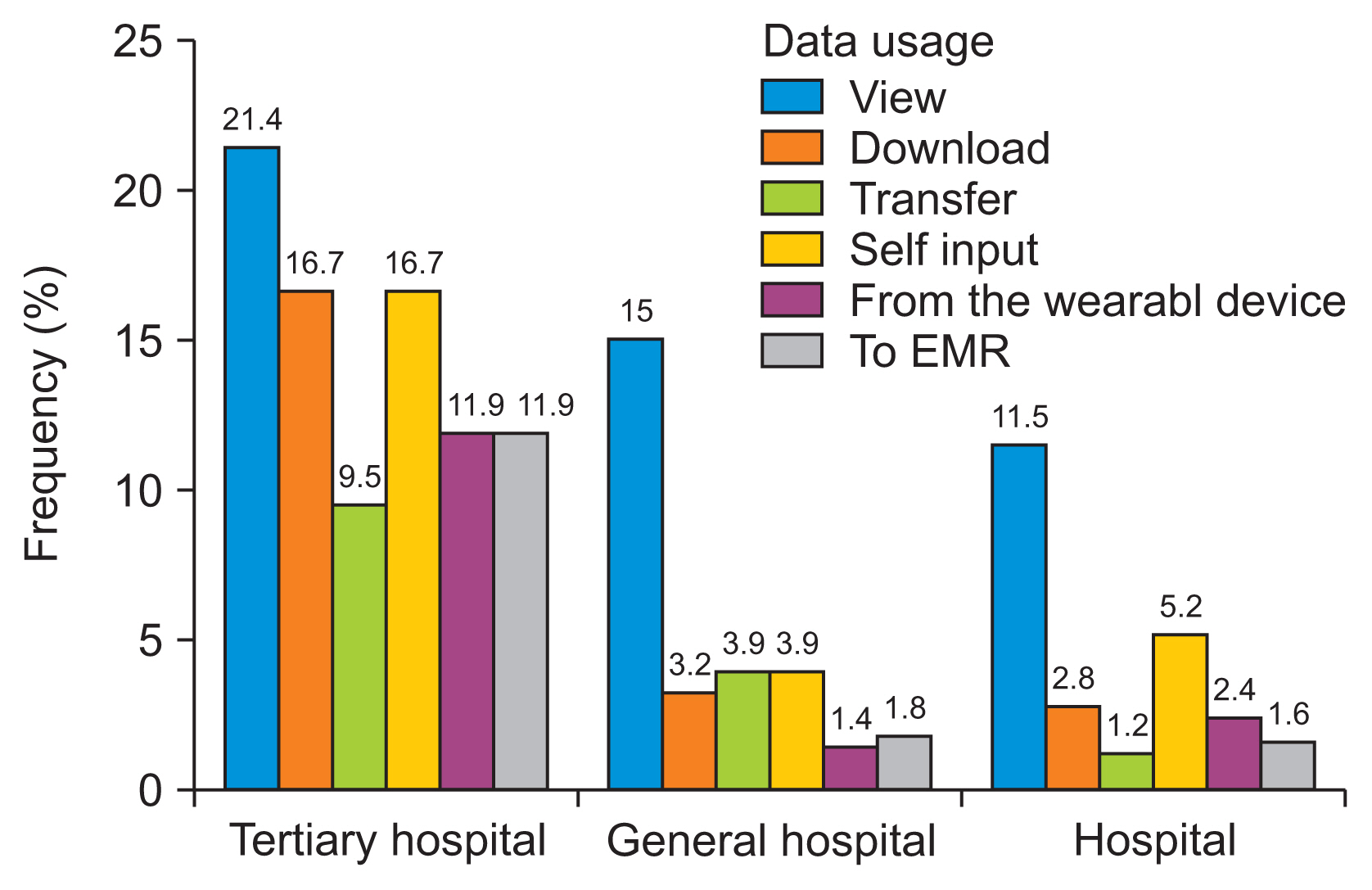

We assessed the extent to which PHRs were used to access and utilize medical data. While there was a notable level of provision for viewing, downloading, and transmitting medical information, the level at which patients directly entered their own health data, transferred information from wearable devices to PHRs, and sent biometric measurements from the PHR to EMRs was found to be comparatively low (Figure 2). In response to the application of integrating biometric measurement data from wearable devices into mobile PHRs, the rates for tertiary hospitals, hospitals with more than 300 beds, those with fewer than 300 beds, and smaller hospitals were respectively 14.3%, 0.8%, 0%, and 0.4%, which are strikingly low. Furthermore, among medical institutions that have not established a feature for integrating biometric data from wearable devices to the PHR system, 33.3% of tertiary hospitals, 18.6% of hospitals with over 300 beds, 19.6% with fewer than 300 beds, and 12.7% of smaller hospitals indicated plans to implement this feature within the next 3 years. Regarding the capability to transmit biometric data from mobile PHRs to EMRs, the adoption rates for tertiary hospitals, those with over 300 beds, those under 300 beds, and smaller hospitals were notably low, at 9.5%, 0.8%, 0.5%, and 0.4%, respectively. Of the medical institutions that had not developed the feature to transfer biometric data from PHRs to EMRs, those considering its adoption within the next 3 years included 31% of tertiary hospitals, 20.3% of hospitals with more than 300 beds, 19% of those with less than 300 beds, and 13% of smaller hospitals.

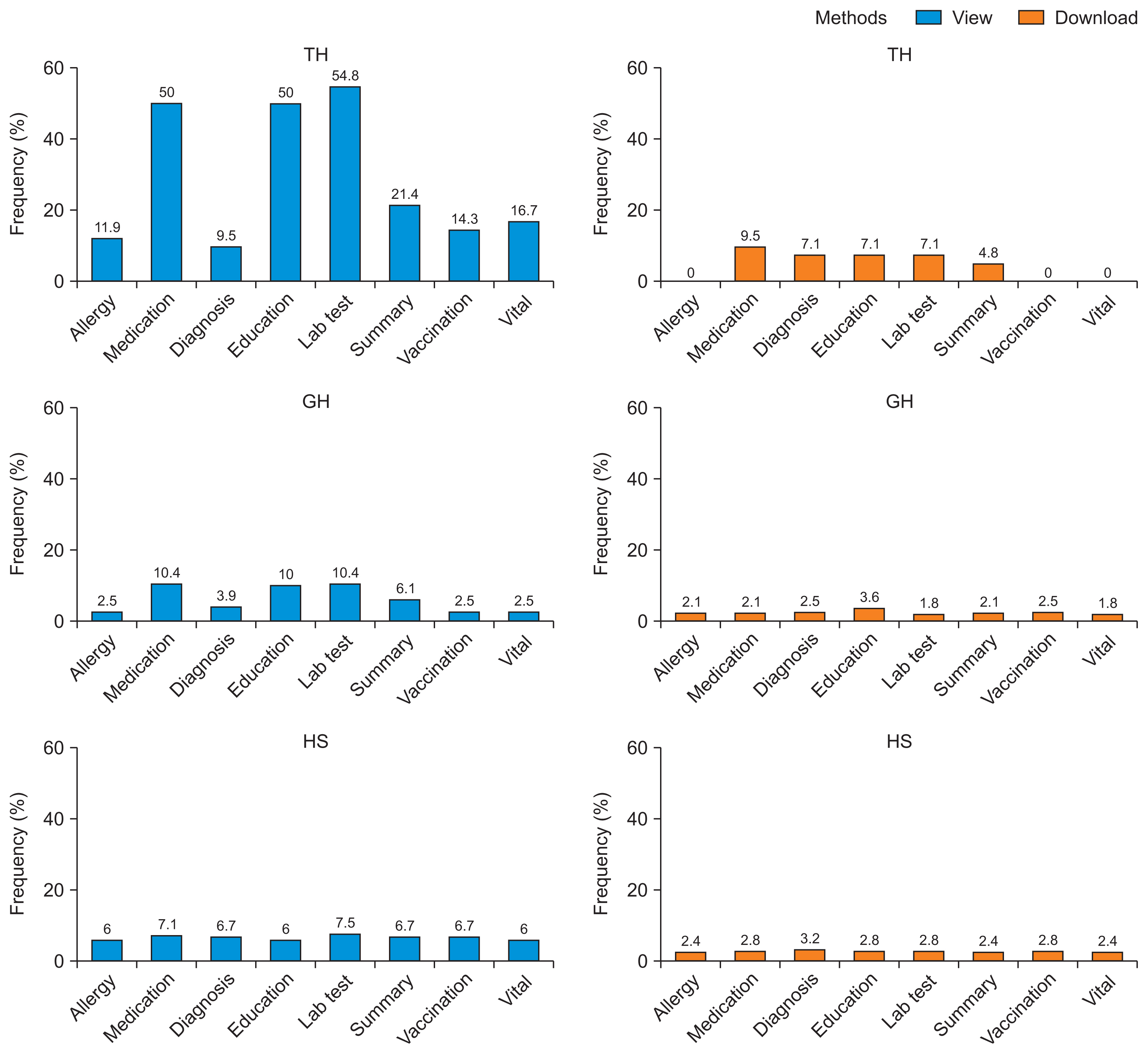

Among the clinical information provided through patient portals or PHRs, test results were the most common, with tertiary hospitals accounting for the highest proportion (54.8%). General hospitals with over 300 beds, general hospitals with fewer than 300 beds, and other hospitals showed considerably lower rates, recording 18.6%, 4.2%, and 7.7%, respectively. Other types of provided clinical data in descending order of prevalence included drug lists, disease and health education, payment information, medical summaries, vital signs, vaccinations, allergies, insurance details, and past medical history. However, in most cases, only the functionality to view the clinical information was provided, with the download capability being almost non-existent. Among tertiary hospitals, prescriptions were the most frequently offered item for download (9.5%), while diagnoses, educational materials, and test results were each offered by 7.1% (Figure 3).

The growing integration of IT in healthcare has led to the widespread adoption of PHRs. This has given patients more control over their own health information, which can be empowering. However, different healthcare systems present unique challenges and opportunities for PHRs. In this study, we observed that although up to 66.7% of tertiary hospitals had adopted PHRs, only 58% of these institutions furnished patients with medical information. Thus, the effective adoption rate, which requires patients to be able to access their personal health data, stood at a mere 38.7% [10]. Notably, smaller hospitals demonstrated remarkably lower levels of both PHR adoption and the provision of medical information, implying a notably low level of adoption among local primary care providers. While the most common types of health information provided were test results and medications, downloading the data was not possible in the majority of cases. Consequently, patients were largely restricted to inquiries, resulting in limitations in computable information exchange. Although the essence of PHR involves enabling patients to access, control, manage, and communicate about their health information while also aiding decision-making, the predominant PHRs in Korea remain deficient in these core functionalities. Instead, they appear to emphasize features that cater to hospital administrative conveniences, such as scheduling, billing, and documentation. Mobile PHR services are widely available and have great potential, but their linkage to lifelog data and use in medical treatment are still low.

Tethered mobile PHRs, developed and provided proactively by medical institutions, began in 2010 [11]. The early 2010s saw the beginning of widespread smartphone distribution in Korea [12], and there was a shortage of commercialized health management apps at that time. With the expansion of smartphone users and the explosion of commercial healthcare apps [13], the functionality of hospital PHRs to manage one’s own health information has decreased in significance. Moreover, records of patients’ daily healthcare activities cannot be linked to EMRs, which limits the ability of medical institutions to provide seamless care. This may be due to negative perceptions regarding using patient-generated health data in medical field [14] and lack of motivation. To this end, it is necessary to report on the patient’s usual condition as an area of treatment, use validated patient-reported outcome measure forms [15], patient-generated health data–EMR linkage, and appropriate data curation according to patient diagnosis and clinical context.

Regardless of the size of the medical institution, the clinical information provided at the highest rate through PHR was found to be lab test results. Lab test results furnish important information for clinical decision-making but are limited information in that they must be combined with other information, such as imaging tests and medical personnel’s observations, to determine the patient’s condition correctly. However, lab test results can be delivered in a relatively small amount of structured data compared to information such as imaging tests, pathological tests, and medical personnel’s observations, and the difference between normal and abnormal can be intuitively judged based on the reference range [16]. Indicators that present mid- to long-term status, such as glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with diabetes, can be used as intuitive goals for patients to manage their own health [17,18]. Additional research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of providing test results and determine whether relevant patient education content is appropriately provided according to test results and how it affects patients’ health management behavior.

PHRs can be sustainably developed and provided only when both the interests of medical institutions and the needs of patients are met. Services such as clinic appointment reservations and document issuance provide convenience to patients by increasing service accessibility, which can help the hospital’s profits by reducing personnel needs and recruiting new patients. Some medical institutions only provide these convenient functions without providing health information. The provision of health information in Korea is still insufficient to meet these mutual needs. In the United States, the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard was developed as part of a government-led emphasis on interoperability, and it became possible to benefit from services such as receiving content based on patients’ self-record information through FHIR-based PHR apps [19] (e.g., Krames On FHIR). In addition, it has been changed to an interoperability promotion program with three levels of meaningful use, and prices are provided based on the 21st Century Cures Act. Patients should be able to experience the usefulness of PHRs led by supporting medical institutions while receiving customized health services, and hospitals should also receive corresponding compensation. Because there is no reward for providing patient information through PHRs, domestic PHRs are still focused on hospital profits, even though patient engagement through PHRs can help improve patient safety and quality of care.

If the interoperability of personal health data is guaranteed, developing services for patients would require fewer resources through open software development. A single medical institution or research institute cannot achieve this alone; it requires government-led initiatives. These initiatives should encourage medical institutions to actively provide patients with medical information through PHRs and to encourage patients to receive services based on their own information. As part of these efforts, in Korea, a PHR based on inter-institution linkage was developed and distributed through the My Health Record app centered on national institutions [20]. This app provides access to diagnosis history, medication history, vaccination history, and more. The data can be linked and utilized in other health apps through app-to-app data linkage. While there is currently no PHR system that allows information exchange between medical institutions, efforts are underway to establish an FHIR-based, subject-centered data movement environment through the MyData project [21]. Furthermore, the revision of the law to include the right to request the transmission of personal health information is drawing attention for its potential impact on the health and medical field.

Currently, the only government support for systems that transmit health information between medical institutions is the Medical Information Exchange Project [22]. My-Healthway (the medical MyData project) represents the first instance of government support for the provision of medical information through PHRs, and the pilot project began in 2021 [20]. Based on the revision of the enforcement ordinance on the right to personal data transmission and portability [23], related research and development projects are expected to increase. However, despite efforts to assist medical institutions in establishing platforms for the provision of medical information through the national MyHealthway project, we are currently unable to guarantee stable and long-term profits akin to those generated by fee-based services. Consequently, it may be challenging to bring about significant short-term changes in the PHR ecosystem that each medical institution has independently constructed. Therefore, an incentive system should be integrated with the MyHealthway project to provide practical assistance in managing national health information.

For hospitals to offer direct or indirect identifiers via PHR and to integrate healthcare services, it is crucial to strictly consider security, consent acquisition, and access authority management. Furthermore, government support is essential for this PHR ecosystem. Beyond national projects aimed at addressing these issues, legal and policy support must be provided to enable the provision of PHR services as an integral part of healthcare services. The FHIR-based MyKanta, utilized by five Nordic countries including Finland, is a national PHR that offers a platform for patients and medical professionals to collaborate. This is achieved by linking health information with social security information [24]. Additionally, Australia’s My Health Record, which was launched in 2012 under the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record Act, now functions to create and provide records for nearly all citizens through an opt-out method [25]. Therefore, to actively utilize PHR services on a national scale, it is necessary to encourage activation through the evaluation and support of basic function fidelity.

We were unable to obtain information on the actual usage or service retention of PHR services. Consequently, this study is limited in its ability to determine which services are most needed by patients and to illustrate how the medical information provided is truly benefiting them. Despite these limitations, this is the first study in which a nationwide survey has been conducted on the provision of personal health information in South Korea. Given that South Korea rapidly implemented and adapted EMR systems, the types of PHRs spontaneously developed by medical institutions could serve as valuable references.

The integration of IT into healthcare has catalyzed the rise of PHRs, promoting patient-centric care. However, our study revealed disparities in PHR adoption, especially in smaller institutions. While tertiary hospitals have taken promising steps in this direction, the provision of comprehensive health data to patients remains limited. In Korea, many PHRs prioritize administrative features over patient empowerment. Although mobile PHRs have the potential for growth, the limited use of comprehensive lifelog data and its medical application highlight existing gaps. Addressing these discrepancies is crucial for maximizing the benefits of PHRs in patient care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HR21C0198).

Figure 2

Status of data transmission through personal health records by hospital category. EMR: electronic medical record.

References

1. Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A.. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns 2016 99(12):1923-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026

2. Perez-Ortiz AC, Villarreal-Garza C, Villa-Romero A, Cruz Lopez JC, Ramirez-Sanchez I, Luna-Angulo A, et al. Pharmacogenetic biomarkers associated with paclitaxel response in Mexican women with locally advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016 34(15_Suppl):e13004.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.e13004

3. Ruhi U, Chugh R.. Utility, value, and benefits of contemporary personal health records: integrative review and conceptual synthesis. J Med Internet Res 2021 23(4):e26877.https://doi.org/10.2196/26877

4. Turvey C, Klein D, Fix G, Hogan TP, Woods S, Simon SR, et al. Blue Button use by patients to access and share health record information using the Department of Veterans Affairs’ online patient portal. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014 21(4):657-63. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002723

5. NHS Digital. An update from NHS England on accelerating citizen access to GP data. 1 November 2022 [Internet]. Lees, England: NHS England; 2023 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/services/nhs-app/nhs-app-guidance-for-gp-practices/guidanceon-nhs-app-features/accelerating-patient-access-totheir-record/update-from-nhs-england

6. Suna T.. Finnish National Archive of Health Information (KanTa): general concepts and information model. Fujitsu Sci Tech J 2011;47(1):49-57.

7. MedMjj project [Internet]. Hague, Netherlands: Med-Mij; 2023 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://medmij.nl/en/home/

8. Lee J, Park YT, Park YR, Lee JH.. Review of national-level personal health records in advanced countries. Healthc Inform Res 2021 27(2):102-9. https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2021.27.2.102

9. Lee K, Seo L, Yoon D, Yang K, Yi JE, Kim Y, et al. Digital health profile of South Korea: a cross sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022 19(10):6329.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106329

10. US Department of Health and Human Services. Personal health records and the HIPAA privacy rule [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/special/healthit/phrs.pdf

11. Lee Y, Shin SY, Kim JY, Kim JH, Seo DW, Joo S, et al. Evaluation of mobile health applications developed by a tertiary hospital as a tool for quality improvement breakthrough. Healthc Inform Res 2015 21(4):299-306. https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2015.21.4.299

12. Kwon H. What has changed in 10 years of smartphone era [Internet]. Seoul: The Chosunilbo; 2017 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2017/09/23/2017092300766.html

13. Park N, Kim YC, Shon HY, Shim H.. Factors influencing smartphone use and dependency in South Korea. Comput Human Behav 2023 29(4):1763-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.008

14. Ye J.. The impact of electronic health record-integrated patient-generated health data on clinician burnout. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021 28(5):1051-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab017

15. Demiris G, Iribarren SJ, Sward K, Lee S, Yang R.. Patient generated health data use in clinical practice: a systematic review. Nurs Outlook 2019 67(4):311-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2019.04.005

16. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Scherer AM, Witteman HO, Solomon JB, Exe NL, Tarini BA, et al. Graphics help patients distinguish between urgent and non-urgent deviations in laboratory test results. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017 24(3):520-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw169

17. Talboom-Kamp E, Tossaint-Schoenmakers R, Goedhart A, Versluis A, Kasteleyn M.. Patients’ attitudes toward an online patient portal for communicating laboratory test results: real-world study using the eHealth impact questionnaire. JMIR Form Res 2020 4(3):e17060.https://doi.org/10.2196/17060

18. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR.. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res 2015 17(6):e148.https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4255

19. Ayaz M, Pasha MF, Alzahrani MY, Budiarto R, Stiawan D.. The Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard: systematic literature review of implementations, applications, challenges and opportunities. JMIR Med Inform 2021 9(7):e21929.https://doi.org/10.2196/21929

20. Korea Health Information Service. What is PHR (Personal Health Record)? [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Korea Health Information Service; 2021 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.k-his.or.kr/menu.es?mid=a20204000000

21. Lee K. Current status of MyData policy and tasks in health and welfare. Health Welf Policy Forum 2021 (301):52-68. https://doi.org/10.23062/2021.11.5

22. Korea Health Information Service. Health information exchange system [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Korea Health Information Service; 2021 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.k-his.or.kr/menu.es?mid=a20207000000

23. Law Times. Introduction to the main contents of the amendment to the enforcement decree of the personal information protection act [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Law Times; 2023 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.lawtimes.co.kr/news/189930

24. Kanta. What are the Kanta services? [Internet]. Helsinki, Finland: Kanta; 2023 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.kanta.fi/en/what-are-kanta-services

25. Healthdirect Australia. About my health record [Internet]. Haymarket, Australia: Healthdirect Australia; 2023 [cited at 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/my-health-record

- TOOLS