|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 29(4); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objectives

Public healthcare data have become crucial to the advancement of medicine, and recent changes in legal structure on privacy protection have expanded access to these data with pseudonymization. Recent debates on public healthcare data use by private insurance companies have shown large discrepancies in perceptions among the general public, healthcare professionals, private companies, and lawmakers. This study examined public attitudes toward the secondary use of public data, focusing on differences between public and private entities.

Methods

An online survey was conducted from January 11 to 24, 2022, involving a random sample of adults between 19 and 65 of age in 17 provinces, guided by the August 2021 census.

Results

The final survey analysis included 1,370 participants. Most participants were aware of health data collection (72.5%) and recent changes in legal structures (61.4%) but were reluctant to share their pseudonymized raw data (51.8%). Overall, they were favorable toward data use by public agencies but disfavored use by private entities, notably marketing and private insurance companies. Concerns were frequently noted regarding commercial use of data and data breaches. Among the respondents, 50.9% were negative about the use of public healthcare data by private insurance companies, 22.9% favored this use, and 1.9% were “very positive.”

Conclusions

This survey revealed a low understanding among key stakeholders regarding digital health data use, which is hindering the realization of the full potential of public healthcare data. This survey provides a basis for future policy developments and advocacy for the secondary use of health data.

Digital health data have become crucial for the advancement of medicine, both scientifically and commercially, and healthcare “big data” drives innovations in medical technology. A surge in the use of big data in biomedicine has brought about growing debates regarding the appropriate utilization of healthcare data, with polarization between viewpoints advocating for the acceleration of use of patient data for knowledge production and perspectives emphasizing potential harm to privacy [1]. To govern the use of healthcare data, along with other personal data, Korean government enacted in February 2020, the Data 3 Law (Personal Information Protection Act, Credit Information Act, Information and Communications Network Act), which allows the use of pseudonymized data without consent from the individual data subjects for scientific research [2]. These changes in the legal framework have paved the way toward more flexible use of health records from public databases for secondary uses [3].

These changes in the regulation of personal healthcare data pose major opportunities for research, as Korea has a centralized healthcare data collection system. The National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC) and the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (HIRA), which are public agencies under the Korean government, collect national health data. For example, the NHIC can provide data from a cohort of 1 million people tracked for 20 years based on their insurance claims, along with socioeconomic data that are used for calculating national health insurance fees. However, the utility of the data was previously limited, as only sampled, anonymized data could be used for academic research purposes prior to the changes in the aforementioned Data 3 Law [4].

In late 2021, five private insurance companies requested data from these two national institutions to conduct research for commercial purposes [5]. HIRA provided data in accordance with the revised Data 3 Law, but the NHIC denied the request and required improvements in the application. The process of submitting a request to HIRA was carried out according to the revised Personal Information Protection Act and the guidelines provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Personal Information Protection Committee [6].

The private insurance companies also requested the NHIC to use pseudonymous data. Over a span of nearly eight years, from 2014, approximately 7,000 research databases were provided, yet only 12 studies were conducted by private companies during this period. Notably, none of these studies were conducted by private insurance companies [7]. In contrast to the decisions made by HIRA, all applications submitted to the NHIC in 2021 by private health insurance companies were rejected. The reason given for these rejections was an “infringement of public interest.” The review panel unanimously agreed that the study’s objective was to develop insurance products on the basis of risk rates calculated by class. However, there was a divergence of opinion regarding whether the purpose of class selection was to exclude the public, who are the data subjects, or to include a larger number of people [8].

The debates surrounding the secondary use of public healthcare data by private insurance companies highlight a significant gap in our understanding of how different stakeholders perceive this type of data. Previous surveys examining awareness and attitudes towards changes in the Data 3 Law and digital healthcare have yielded significantly different results. A government-conducted survey showed a high level of awareness and acceptance of legal changes and personal data sharing, with 71.2% and 77.4%, respectively. In contrast, a survey conducted by civil society revealed opposing views, with only 18.1% and 29.5%, respectively [9,10]. Studies and surveys from the United States and Europe indicate that the public has limited understanding or awareness of how their public health records are used. Furthermore, there is a general reluctance to share healthcare data with private entities, and a highly negative attitude towards the secondary use of healthcare data by private insurance and marketing companies. However, it is important to note that most of these studies utilized focus group interviews and did not represent the broader population [11–13].

The current situation reveals a significant disparity between public attitudes and the existing legal framework regarding the secondary use of public healthcare data. As the ultimate data subjects, citizens’ acceptance and agreement are crucial for the successful collection and utilization of this type of data. This necessitates an understanding of the individual data and the subject’s perspective on healthcare data sharing. To date, no study in Korea has specifically examined public perception towards the collection and use of public healthcare data, particularly the secondary use of pseudonymized data under the enactment of Data 3 Law. This study aimed to survey public attitudes towards the secondary use of public healthcare data in Korea, with a particular emphasis on data sharing among various public and private entities. Given that the survey encompasses a representative sample of the population of Korea, the results will highlight discrepancies between public perception, the legal framework, and actual data-sharing practices.

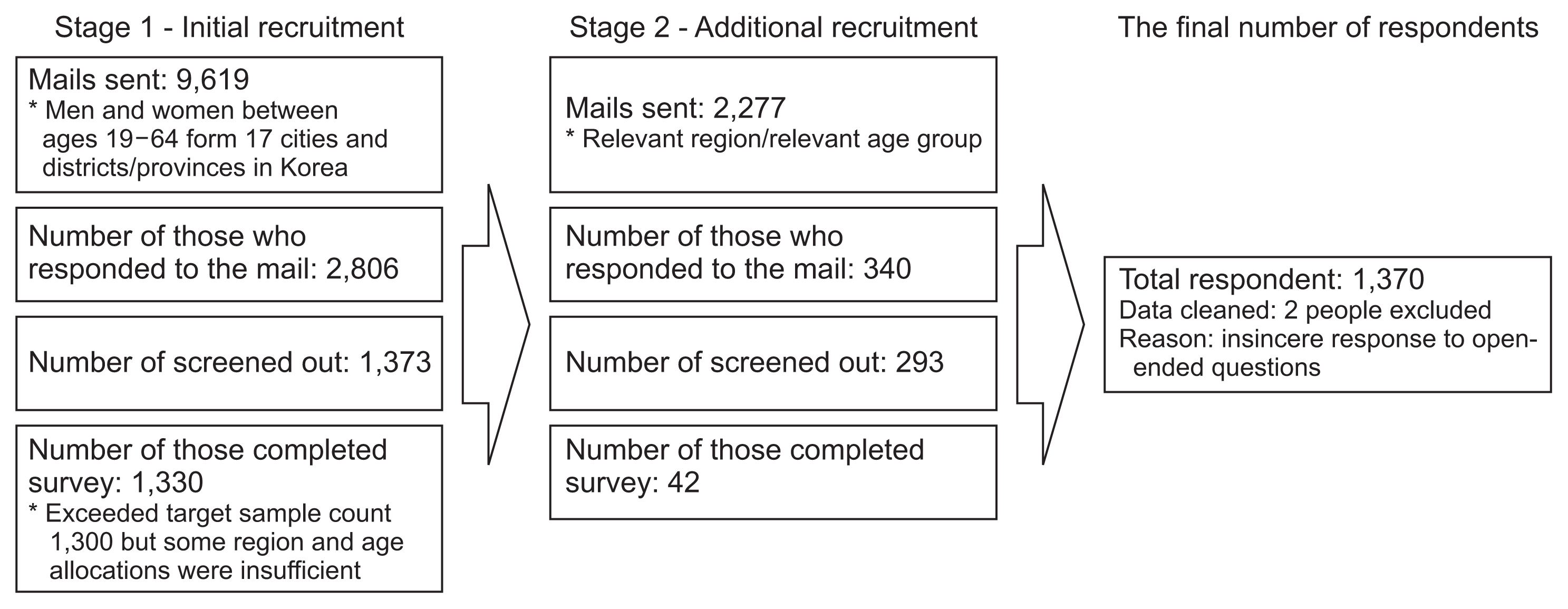

This was a nationwide online survey, with a sample of adults aged 19–65 selected using post-stratification based on gender, age (in 5-year intervals), and 17 administrative divisions. The selection was based on the official census data from August 2021. Out of 9,619 eligible cases pre-registered to the Gallup Korea Panel, a survey questionnaire link was sent via mail. Those who did not complete the questionnaire were screened out. In the first round, 1,330 participants completed the survey. However, there was a lack of representation of specific regions and age groups. To form a representative population, part of the recruitment was outsourced to an external pre-registered panel of 2,277. A total of 42 participants completed the questionnaire and were included in the final analysis. The survey was conducted from January 11 to 24, 2022. Figure 1 illustrates the methods of recruitment and processing of the participants.

The survey questionnaire focused on several key areas: (1) awareness and attitudes towards the collection and use of public healthcare data, including changes in law and current practices; (2) attitudes towards the secondary use of public healthcare data by various stakeholders, such as government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, private insurance companies, and information technology (IT) companies; (3) attitudes towards the extent of public healthcare data utilization, including its use by the government for public good and by private entities for profit; (4) attitudes towards the purpose of utilizing public healthcare data, which could include public health policy development, academic research, product development, private insurance product development, and marketing; (5) attitudes towards the use of pseudonymized data, including the need for consent, privacy protection, and data ownership; and (6) demographic information, such as age, gender, income, health condition, private insurance coverage, and hospital usage. Certain sections of the survey included brief explanations of terminology and the current legal and policy framework for healthcare data exploitation. Each section of the questionnaire provided a detailed explanation of key terms (public healthcare data, Data 3 Law, and pseudonymized data) to make it easier for participants to understand.

The questionnaire was reviewed in consultation with a variety of experts in the field of public healthcare data utilization. This included designated officials responsible for data use in the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and HIRA, researchers specializing in healthcare data from private insurance companies, scholars of medical ethics in academia, and activists from civil societies who were part of the review panel for public healthcare data use in HIRA and NHIS. Each expert provided feedback on the questionnaire, with the aim of minimizing bias in the questions. This feedback was gathered through both email and in-person discussions. Based on the experts’ feedback, the questions were modified and rearranged prior to the questionnaire’s finalization.

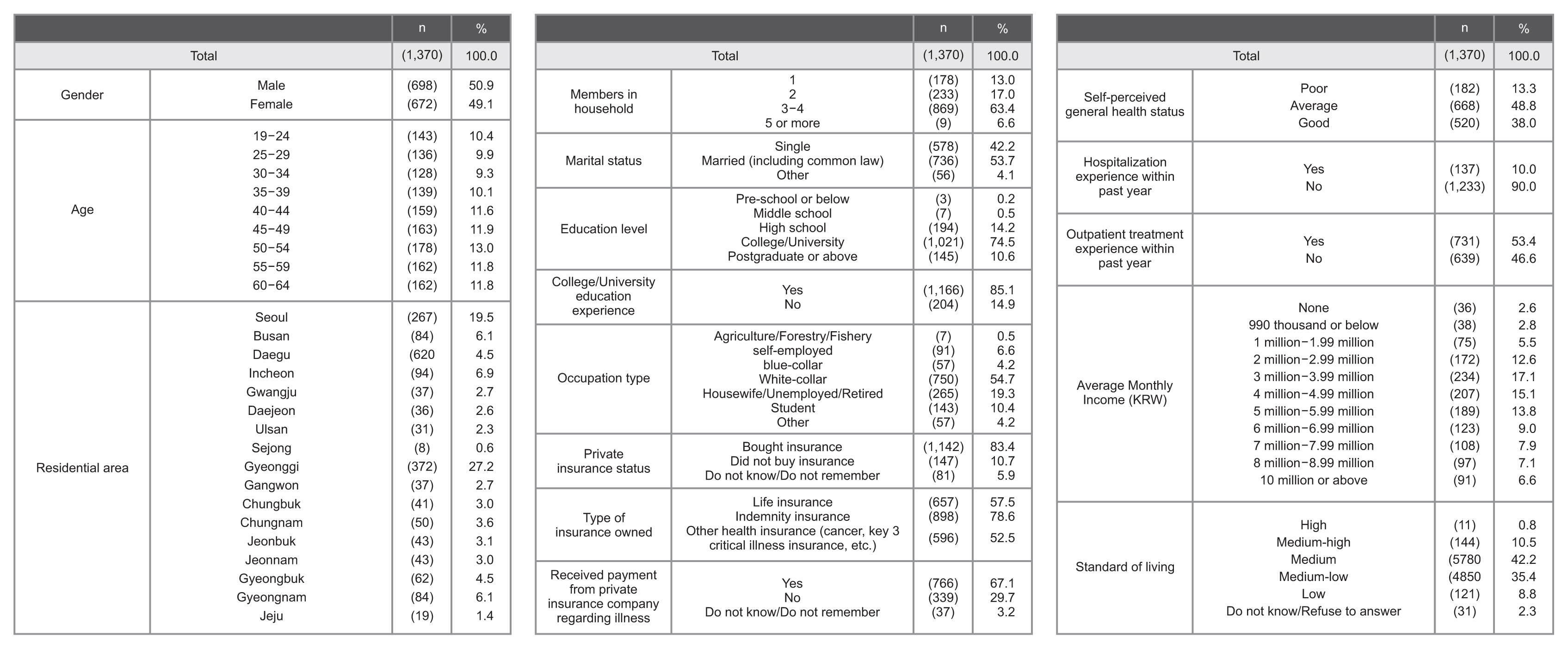

A total of 1,370 participants were included in the final survey analysis. The distribution of gender and age groups was balanced, with an even allocation between males and females, and across age groups ranging from 19 to 64 (Figure 2). Among the respondents, 83.4% had private insurance coverage, and 67.1% had previously filed a private insurance claim. Ten percent of respondents had been admitted to a hospital before, while 53.4% had visited outpatient clinics.

Respondents were generally aware of the changes and data protection law (61.4%) and the use of public healthcare data by government, industries, and researchers (72.5%). The willingness to provide consent for the use of personal data was highest for public healthcare data as anonymized sampled data (65.6%), with less support shown for anonymized raw data (59.0%), pseudonymized sample data (56.9%), and pseudonymized raw data (51.8%).

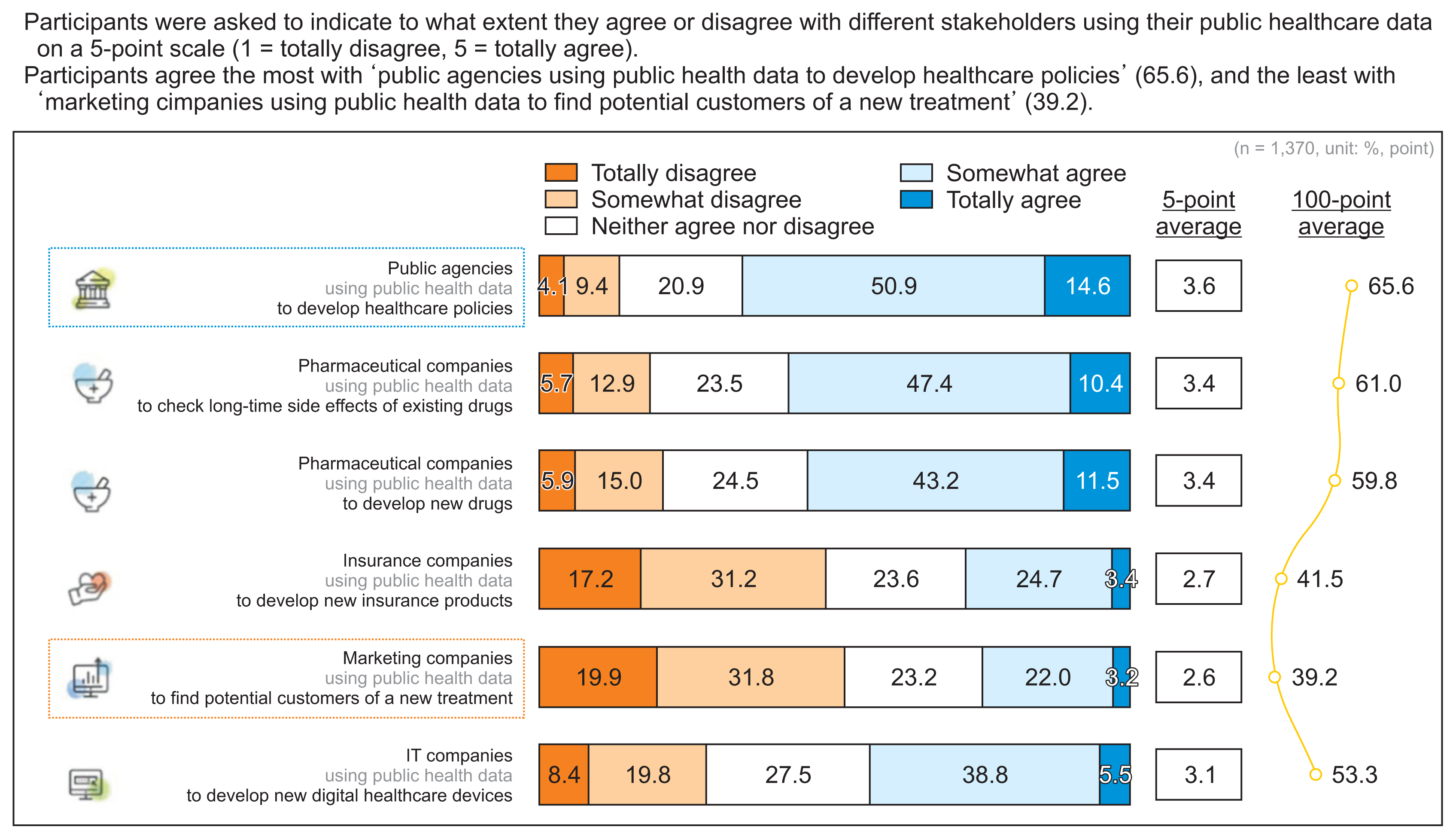

Respondents showed marked differences in their attitudes toward public healthcare data use according to the entities in question. Most respondents were in favor of public agencies (65.6), pharmaceutical companies (61.0 for side effect surveys and 59.8 for novel drug development), and IT companies (53.3 for the development of new digital health devices) using the data for secondary purposes. However, there was disagreement among respondents about allowing private insurance companies to access public healthcare data for the development of new insurance products (41.5), and marketing companies using the data to search for potential customers (39.2) (Figure 3). Respondents were most supportive of public agencies using the data to develop healthcare policy, while they were least supportive of marketing companies using the data to identify potential customers for a new treatment.

Regarding the extent of accessibility of public healthcare data, respondents tended to agree with the use of data by both public agencies (65.2) and industries (62.1). However, a significant proportion of respondents opposed access to the data even if a lack of data access stops research (38.1%). There was a mixed response regarding data use, with 52.1 stating, “I do not want public healthcare data to be utilized in any cases.” Only 34.9 supported the complete openness of public healthcare data. When asked about the use of the data by either public or private entities, respondents favored public agencies (65.2) and were least supportive of its use for commercial purposes by private entities (34.8). The perception of respondents towards the use of public healthcare data by private entities became more favorable when it was used for the public good rather than for profit (47.5).

The highest level of agreement regarding the purpose of data use was found in relation to public agencies, both for the improvement of services (65.3) and the equitable distribution of public goods (63.8). Respondents indicated that academic institutions and private companies could utilize the data for academic research purposes (65.1 and 52.4, respectively); however, there was a significant drop in agreement when data use was intended for commercial purposes (44.5 and 38.3, respectively). Regardless of the entity involved, respondents demonstrated less confidence in data use for commercial purposes and showed a preference for its use in serving the public good.

Respondents strongly agreed on the necessity of obtaining prior consent, even when the public healthcare data are in a pseudonymized form (75.8). There was a significantly lower level of agreement regarding the waiver of consent if pseudonymized data are used to generate generalized knowledge. Notably, there was a lack of confidence in privacy protection (46.1) and safety from re-identification (48.4). Concerns were raised about privacy and potential data leakage (75.2), as well as the risk of re-identifiability (64.9). Respondents expressed a strong desire to maintain control over their data (70.4), yet they demonstrated a relatively low sense of ownership over data generated within medical facilities (45.2) (Figure 4).

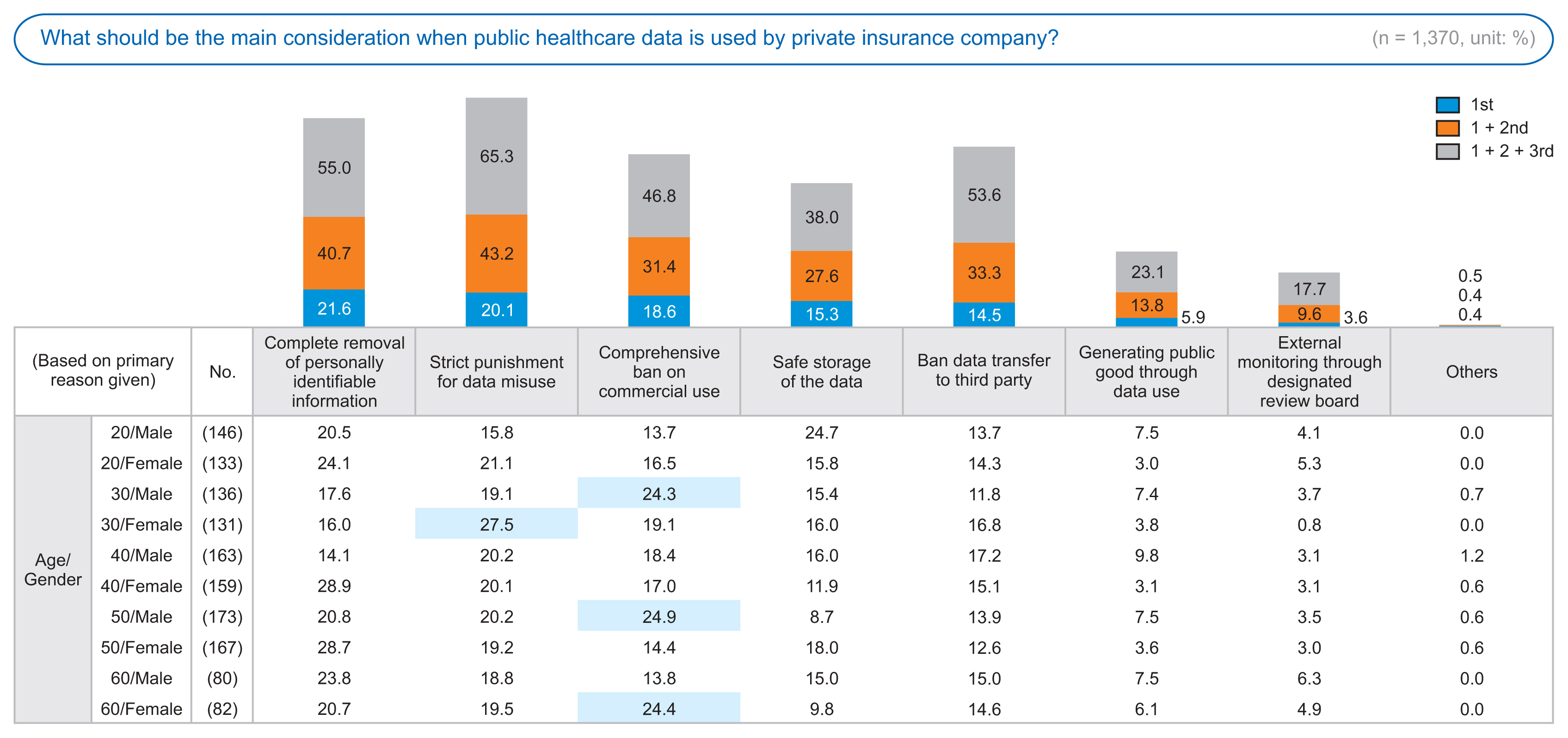

Respondents showed negative attitudes towards the use of public healthcare data by private insurance companies, with 50.9% expressing negativity. Only 22.9% were in favor, and a mere 1.9% responded with a “very positive” attitude. The primary concerns were potential commercial exploitation of the data (36.1%), privacy issues (28.2%), and perceived consumer disadvantage (11.6%). Those who responded positively cited reasons such as the potential for multiple applications of reliable data (14.6%), the generation of reasonable fees (10.8%), and the opportunity for new product development (10.8%). Interestingly, respondents who claimed a neutral stance primarily expressed reasons that were unfavorable towards the use of data by private insurance companies, including commercial use (28.1%), privacy concerns (16.7%), and negative perceptions of private insurance companies (11.4%). The primary consideration for the use of public healthcare data by private insurance companies was the complete removal of personally identifiable information (21.6%) (Figure 5). This was followed by the implementation of strict punishments for data misuse (20.1%), and a comprehensive ban on commercial use (18.6%). These concerns varied depending on age group and gender. For instance, men in the age group of 30 to 39 believed that a comprehensive ban on commercial use should be the primary concern (24.3%), whereas women in the same age group prioritized strict punishments for data misuse (27.5%).

The findings of this study fundamentally diverge from those of previous research conducted in other countries. Whereas most earlier studies utilized a small, random selection of participants, our sample was comprised of a panel representative of the South Korean population, providing a comprehensive view of public perceptions. Consequently, some researchers have inferred that younger individuals exhibit a more positive attitude toward data sharing, openness, and usage. Although the varying contexts make it challenging to definitively refute these assertions, our results indicate that young people do not inherently react favorably to the public disclosure of their data.

In accordance with a prior survey regarding changes in the Data 3 Law, individuals demonstrated a strong understanding of the changes in the legal framework. However, they expressed a preference for their data to be shared as anonymized samples rather than as pseudonymized raw data. Despite this high level of awareness, it is important to highlight that many respondents believed that individual consent should be obtained before pseudonymized data are used for scientific purposes, regardless of the recent legal changes.

In this survey, male participants aged 30 to 39 demonstrated a negative perception towards the secondary use of public healthcare data by any entity, compared to other gender and age groups. Respondents who had been admitted to a hospital within the past year generally exhibited a positive attitude towards the use of data by both private insurance and marketing companies. These individuals also tended to support the complete openness of data, as well as its use by private entities for both public benefit and profit. However, respondents who held private insurance were hesitant to allow private entities to profit from the data. These individuals displayed a significantly negative perception towards the use of public healthcare data by private companies for profit and were more inclined to favor its use by public agencies for public benefits. The experience of hospital admission was identified as a factor influencing positive attitudes towards the use of public healthcare data in patent registration for profit by private entities. Both hospital admission experience and private insurance were factors that influenced attitudes towards the use of pseudonymized data. Individuals with private insurance were found to have greater concerns regarding re-identifiability and data leakage. Those with hospital admission records also expressed concerns about data protection, but were more supportive of waiving consent when pseudonymized data are used.

Regarding the sharing and use of public healthcare data, individuals were generally accepting when such data were utilized by public institutions. However, they expressed disagreement when it came to the use of these data for marketing or the development of private insurance products. The extent of data use yielded mixed results; while many agreed with data use for the public good, a significant number refused to share their data under any circumstances. Overall, individuals were amenable to the sharing and use of their data by public agencies for the public good, but they were opposed to the secondary use of their data for commercial purposes by private entities. This opposition could be attributed to heightened concerns about data leakage or breaches of privacy, as indicated by the survey results.

However, both HIRA and NHIC customized databases must be utilized within a closed analysis center, while sampled databases can be accessed through a remote analysis system. For research conducted by private companies, only sampled databases are provided, and these must also be used within a closed analysis center, similar to academic research. Contrary to public perception, this setup significantly minimizes the risk of data leakage.

In light of recent debates about private insurance companies using public healthcare data, there is a general disapproval of such usage by these companies. The primary concern is that this public data will be exploited for commercial purposes, with data misuse and leakage being additional worries. This underscores the public’s preference for the “public good” and a firm resistance to its commercial exploitation. However, to fully comprehend this stance, further surveys and analysis are needed to clarify the respondents’ exact interpretation and understanding of “public good.”

Following the 2020 revision of the Personal Information Protection Act and the Credit Information Protection Act, also known as the Data 3 Law, promotional activities have been sparse. There has been no clarification regarding the potential benefits for individuals if pseudonymous data were to be utilized for commercial research. Consequently, it is imperative to improve public comprehension of these new laws and policies.

Our study reveals a possible way forward. The panel demonstrated a generally positive and favorable attitude towards the term “public.” However, their response to the terms “for-profit” and “private” was negative. Consequently, a public relations strategy is required to clarify the definition of “public” to the general populace, and to persuade them that “for-profit” and “private” can also pertain to the public good.

The analysis of changes in public attitudes towards public healthcare data following the revision of the Data 3 Law was somewhat limited given a lack of baseline data. As such, a follow-up survey will be necessary to monitor long-term shifts in societal perception in response to changes in the legal system. Additionally, conducting a targeted survey among healthcare professionals could help to further clarify the existing disparities between the groups.

This study revealed a persistent discrepancy between public attitudes and acceptance concerning the secondary use of pseudonymized public healthcare data, despite recent legal changes permitting the scientific use of such data. This discrepancy could potentially undermine the general utilization of health data, as public participation is crucial to successful health data collection. Furthermore, this could impede future endeavors related to the secondary use of health data by both public and private entities, as public refusal may increase. This issue could be mitigated through active engagement and advocacy, which would help stakeholders better comprehend the actual benefits and risks associated with the use of public healthcare data. Previous studies have indicated that the process of participating in a focus group interview can familiarize participants with the terminology and procedures related to healthcare data use, thereby reducing discomfort towards the utilization of such data [13].

In this survey, participants expressed a willingness to cooperate with the use of their data, but harbored concerns about privacy protection and the potential misuse of public assets. As both participants and providers of healthcare data, members of the public should be given access to the policymaking process regarding the use of their data. Medical professionals are not mere observers in this matter, but active contributors in the generation and utilization of health data. As custodians of such medical knowledge and resources, they should play a more proactive role in discussions about the use of public healthcare data. The Korean government has initiated the National Project of Bio Big Data plan, aiming to establish a national digital library of health data by 2028. A significant simplification of the consent process is a key feature of this project.

With rapid advances in big data projects and the secondary use of health data, the findings of this survey imply that lawmakers possess a limited understanding of public perception regarding the collection and use of digital health data. Furthermore, despite the immense potential of properly used health data to enhance population health, there is a notable lack of initiative for data sharing at the administrative level. Concurrently, the general public demonstrates a limited understanding of changes in privacy laws and the actual risk of data leakage, which makes them hesitant to share their data. The discrepancies identified in this survey could impede the full potential of public healthcare data. Therefore, this study underscores the need for active participation by all stakeholders in this discussion.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Healthcare AI Convergence Research & Development Program through the National IT Industry Promotion Agency of Korea (NIPA) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (No. 1711120339).

References

1. Khoury MJ, Ioannidis JP.. Medicine. Big data meets public health. Science 2014 346(6213):1054-5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa2709

2. Korean Law Information Center. Personal Information Protection Act [Internet]. Sejong, Korea: Korean Law Information Center; 2020 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW//lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=213857&chrClsCd=010203&urlMode=engLsInfoR&viewCls=engLsInfoR#0000

3. National Assembly Budget Office. Public health data budget analysis. Seoul, Korea: National Assembly Budget Office; 2021.

4. Aljunid SM, Srithamrongsawat S, Chen W, Bae SJ, Pwu RF, Ikeda S, et al. Health-care data collecting, sharing, and using in Thailand, China mainland, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Malaysia. Value Health 2012 15(1 Suppl):S132-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.004

5. Kim NH. 6 Private health insurance companies acquired HIRA approval for public health data [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Medical Observer; 2021 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.monews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=305625

6. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Instruction on use of public data [Internet]. Wonju, Korea: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; c2023 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.hira.or.kr/dummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA070001000430

7. Kim NH. NHIC promotes big data use by industry [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Medical Observer; 2022 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.monews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=310972

8. Jung YS. NHIC denies request of private insurance [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Korean Hospital Association; 2021 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.khanews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=213465

9. The Presidential Committee on the 4th Industrial Revolution. Result of survey on Data 3 Law [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: The Presidential Committee on the 4th Industrial Revolution; 2020 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.4th-ir.go.kr/4ir/detail/1131?boardName=

10. Korean Confederation of Trade Unions. Report on survey on public perception in amendment of privacy protection law [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Korean Confederation of Trade Unions; 2019 [cited at 2023 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.hrarchive.or.kr/theme/basic/list.php?search_content=&make_where=&make_start_date=&make_end_date=&category=&shape=&detail_url=board_list&no=19042&page=11&develop_mode=

11. Ghafur S, Van Dael J, Leis M, Darzi A, Sheikh A.. Public perceptions on data sharing: key insights from the UK and the USA. Lancet Digit Health 2020 2(9):e444-e446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30161-8

12. Skovgaard LL, Wadmann S, Hoeyer K.. A review of attitudes towards the reuse of health data among people in the European Union: The primacy of purpose and the common good. Health Policy 2019 123(6):564-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.03.012

13. Trinidad MG, Platt J, Kardia SLR.. The public’s comfort with sharing health data with third-party commercial companies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2020 7(1):149.https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00641-5

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- Scopus

- 1,341 View

- 145 Download

- Related articles in Healthc Inform Res

-

Survey on the Consumers' Attitudes towards Health Information Privacy2007 December;13(4)