|

|

- Search

| Healthc Inform Res > Volume 29(1); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Methods

A systematic search was conducted of the following databases: Web of Science/ Core Collection, Scopus, PubMed, Embase, and Ovid/ MEDLINE until March 2021. Cross-sectional studies reporting the prevalence of nomophobia in undergraduate or postgraduate university students that assessed nomophobia with the 20-item Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) tool were included. Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were performed in duplicate. A meta-analysis of proportions was performed using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using sensitivity analysis according to the risk of bias, and subgrouping by country, sex, and major.

Results

We included 28 cross-sectional studies with a total of 11,300 participants from eight countries, of which 23 were included in the meta-analysis. The prevalence of mild nomophobia was 24% (95% confidence interval [CI], 20%–28%; I2 = 95.3%), that of moderate nomophobia was 56% (95% CI, 53%–60%; I2 = 91.2%), and that of severe nomophobia was 17% (95% CI, 15%–20%; I2 = 91.7%). Regarding countries, Indonesia had the highest prevalence of severe nomophobia (71%) and Germany had the lowest (3%). The prevalence was similar according to sex and major.

Nomophobia is the fear of not being able to use a mobile phone and/or the services it offers [1]. The prevalence of nomophobia ranges from 6% to 73% among various populations [2]. This prevalence is predicted to increase, becoming a major problem, due to the massive use of smartphones; likewise, the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has increased the time of use of these devices [3].

This problem occurs more frequently in adolescents and young adults [4], a population that corresponds to university students, who present a high prevalence of severe nomophobia [5]. The major problems of nomophobia in this population are poor academic performance and sleep disturbances [6], because nomophobia can be associated with anxiety, stress, dependence, low self-esteem, social problems, and fear, which is followed by feelings of frustration and obsessive thoughts, among others [7]. In addition, excessive cell phone use is associated with harmful effects on physical health such as repetitive motion injuries, pain in elbows, wrists, back, shoulders and thumb, index and middle fingers, as well as migraines and numbness due to constant mobile phone use [8,9]. Furthermore, a lack of confidence, low self-esteem, and lack of social skills when making social connections cause more dependence on mobile phones [10]. It should also be taken into account that demanding academic and personal lives make the use of these devices indispensable [10,11].

It is important to determine the prevalence of nomophobia, as it is a global problem. Systematic reviews of the prevalence of nomophobia have been carried out; however, they are limited in evaluating general populations, and none used uniform criteria to establish the prevalence of nomophobia [2,5]. Therefore, the aim of the present review was to synthesize previously reported data on the prevalence of nomophobia, as well as to establish its prevalence according to severity in university students.

We performed a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines 2020 [12]. The study protocol was registered on PROSPERO (No. CRD42021230740).

Cross-sectional studies reporting the prevalence of nomophobia in undergraduate or postgraduate university students were included. Studies that assessed nomophobia with the 20-item Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) tool developed by Yildirim and Correia [13] were considered. We chose this instrument as an inclusion criterion, since it is the most widely used validated scale [14] and divides nomophobia into absent (20 points), mild (21–60 points), moderate (61–100 points) and severe (101–120 points) [A1]. Studies with fewer than 30 participants, duplicate populations, clinical trials, case-control studies, case reports, editorials, commentaries, clinical practice guidelines, opinions, and reviews were excluded.

A systematic search was conducted in five databases: Web of Science/Core Collection, Scopus, PubMed, Embase and Ovid MEDLINE on March 16, 2021. No language or publication date restrictions were applied. The full search strategy for each database is available in Supplementary Table S1. We also screened the reference list of all included studies for additional eligible studies.

The identified references were exported to the Rayyan program [15] where duplicates were manually removed. Subsequently, two authors (KGT and SDCD) screened articles by titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles for inclusion. Selected studies then underwent full-text screening (KGT and SDCD). These processes were conducted independently, and a third author (DRSM) resolved discrepancies by reaching a consensus for the final decision.

Two authors (KGT and SDCD) independently extracted the following data of interest using a Microsoft Excel sheet: author, year of publication, country, sample size, setting (undergraduate, postgraduate), age, sex, major, cut-off points used in the scale, and the prevalence of nomophobia overall and by severity. A third author (DRSM) resolved any discrepancies.

Two authors (KGT and SDCD) independently assessed the methodological quality of prevalence studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool [16]. A third author (DRSM) resolved discrepancies at this stage. This scale has nine items with possible answers of “yes,” “no,” and “unclear” if the study did not have enough data to reach a conclusion about the item. For the quality score of the study, 1 point was given if it complied with each item, and 0 if it did not comply or did not make the item clear. For the prevalence analysis according to the risk of bias, a total score of 0–3 was considered as indicating low methodological quality, 4–6 moderate quality, and 7–9 high quality.

We calculated the pooled prevalence of nomophobia in university students, using a random-effects model, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the exact method with the Freeman-Tukey double-arcsine transformation to stabilize variance. Studies using standardized cut-off points for the NMP-Q scale were included in the meta-analysis. To assess heterogeneity and its sources, we used the Cochrane Q statistic and the I2 test, and we performed subgroup analyses according to country, sex, and major. We also performed a sensitivity analysis according to the risk of bias of the studies. We also assessed publication bias with the Egger test, considering p < 0.05 as indicating the presence of publication bias. The analyses were performed with Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

After removing duplicate records, we identified 230 studies through database searching. We reviewed 78 full-text studies and selected 24 after applying the inclusion criteria. We also identified four studies by checking the references of the included articles. We finally included 28 studies in the review (Figure 1). Reasons for the exclusion of the full-text articles reviewed are given in Supplementary Table S2.

Twenty-eight studies with a total of 11,300 participants were chosen (Table 1, Appendix 1). With respect to countries, 15 studies were conducted in India [A2,A5–A8, A12,A13,A19–A21,A23–A25,A27,A28], six in Turkey [A3, A10,A11,A15,A17,A26], and one each in Oman [A9], the United States [A14], Pakistan [A4], Kuwait [A16], Saudi Arabia [A18], Indonesia [A22], and Germany [A1]. In terms of populations, the majority had a mean age between 19 to 22 years, and 23 included undergraduate university students [A1,A2–A6,A8,A10–A15,A17–A22,A24,A26–A28], one included graduate students [A23], and four were conducted in both populations [A7,A9,A16,A25].

The majority of studies evaluated students majoring in health-related professions (medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, dentistry, and pharmacy, among others) while six studies did not mention the majors evaluated [A4,A5,A9,A16,A25,A26].

Regarding cut-off points, most studies classified nomophobia into four groups (absent 20; mild 21–59; moderate 60–99; severe 100–120), three studies used statistical methods to divide nomophobia into present and absent [A21,A23,A26], one used cut-off points to classify participants into two groups (absent < 59; present 60–100) [A6], and one study did not specify this information [A15].

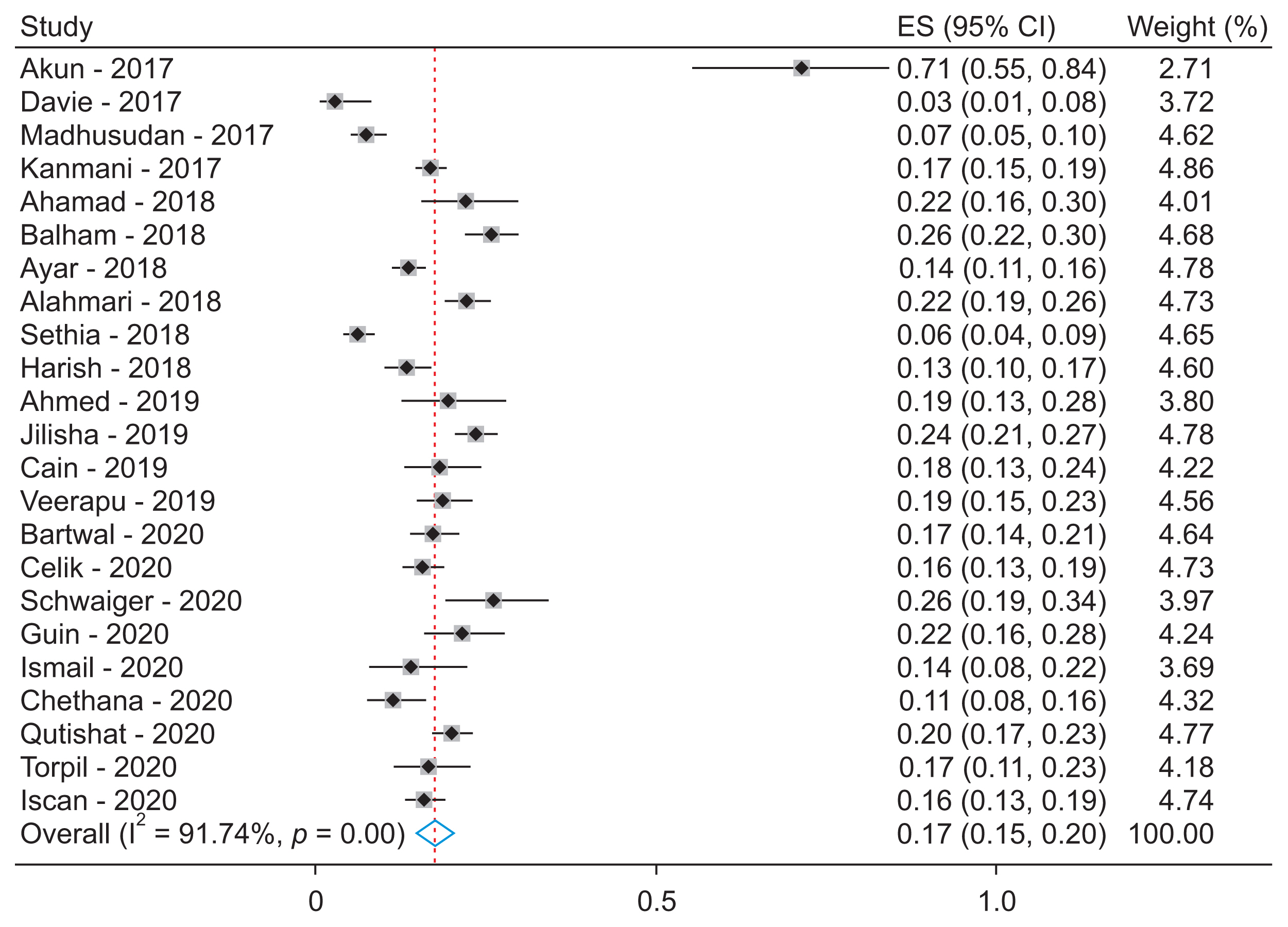

A meta-analysis was performed with the 23 studies that presented the prevalence of nomophobia in university students using standardized cut-off points to classify the condition as absent, mild, moderate, and severe [A1,A2–A5,A7–A14,A16–A20,A22,A24,A25,A27,A28]. The overall prevalence was close to 100%. According to severity, the prevalence of mild nomophobia was 24% (95% CI, 20%–28%; I2 = 95.3%), that of moderate nomophobia was 56% (95% CI, 53%–60%; I2 = 91.2%), and that of severe nomophobia was 17% (95% CI, 15%–20%; I2 = 91.7%). High heterogeneity was consistently evident in the meta-analysis (Figures 2–4).

In addition, the prevalence was assessed according to country, sex and major. Among the nine countries studied, Indonesia had the highest prevalence of severe nomophobia (71%; 95% CI, 55%–84%) and Germany had the lowest prevalence (3%; 95% CI, 1%–8%) [A1,A22]. In relation to major and sex, the prevalence was similar between categories, albeit with high heterogeneity (Table 2).

Regarding risk of bias, fewer than half of the studies met the items of “appropriate sampling frame,” “appropriate sampling,” “adequate sample size,” and “analysis conducted with sufficient sample coverage.” However, the majority met the items “validated methods for the identification of nomophobia,” “condition measured in a standard and reliable way for all participants,” and “appropriate statistical analysis” (Supplementary Table S3). When performing a sensitivity analysis according to risk of bias, we found that the prevalence rates among low-, moderate-, and high-quality studies were similar.

In the present study, we found that the overall prevalence of nomophobia in university students was approximately 100%. According to the severity of nomophobia, we found that one in four participants had mild nomophobia, more than half had moderate nomophobia, and approximately one in five participants had severe nomophobia. In addition, we evaluated the prevalence according to country, sex, and major; however, we found no differences between them.

Nomophobia is the fear of not having access to a mobile device or feeling disconnected [14]. We found two systematic reviews that assessed the prevalence of nomophobia. The first aimed to report on the prevalence of nomophobia and differences between sex and age; however, it did not perform a meta-analysis [2]. The second of these studies meta-analyzed the prevalence of nomophobia by population type, instrument, and severity [5]; however, the diagnostic criteria and severity classification used were not uniform. Therefore, we focused on evaluating the prevalence of nomophobia in university students, including studies that assess nomophobia with the NMP-Q scale. Furthermore, in the meta-analysis, we only included studies using standardized cut-off points for defining nomophobia as absent (20), mild (21–59), moderate (60–99), and severe (100–120). Regarding prevalence, the aforementioned systematic review found that the prevalence of severe nomophobia in university students was 25.5% (95% CI, 18.5%–34.0%; I2 = 97.0%) [5]. This overall prevalence is slightly higher than that found in the present study; however, the confidence intervals overlap. However, that study could not be compared regarding the other grades (mild and moderate) since it did not present the corresponding results.

When analyzing the prevalence rates according to major and sex, we found that they were similar. This last finding differs from the previous literature, where it was described that women were more likely to have nomophobia [2]. However, when evaluating prevalence rates by country, we found that most studies were from India, and the study that presented the highest prevalence of severe nomophobia was from Indonesia [A22].

In addition to the characteristics assessed, the prevalence of nomophobia and its severity can vary due to various factors.

The results of the research carried out highlight a high prevalence of moderate and severe nomophobia. The importance of nomophobia lies in the fact that it is associated with mental health problems, such as increased stress, anxiety, irritability, insomnia and depression, and can cause personality disorders and problems of self-esteem, loneliness or social isolation, and unhappiness [17]. It can also cause cognitive and motor impulsivity, whereby a person cannot concentrate on activities or performs them without thinking [6]. This can especially affect university students, in whom it has previously been reported that levels of nomophobia have a positive relationship with anxiety, stress and depression, and also interfere with their interpersonal relationships and academic performance, since a higher level of nomophobia was associated with worse academic performance [18]. It has even been proposed to include this phobia in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) fifth edition, due to its growing importance [19]. To address this problem, online educational interventions with interactive interfaces have been shown to decrease nomophobia; however, studies evaluating other types of interventions to address this problem are still lacking [2,19].

The included studies had limitations. We found high heterogeneity despite uniformity in the NMP-Q cut-off points used to classify nomophobia severity. Because five studies did not use standardized cut-off points to define nomophobia, they were excluded from the quantitative synthesis. This heterogeneity could be explained by differences in the sampling frame between the included studies. Only three articles conducted research at more than one university and in at least two majors. Furthermore, only six studies used random sampling or surveyed the entire population and only nine reported the sample calculation. Similarly, the diversity of majors and countries included in the meta-analysis would contribute to the high heterogeneity. Other factors that could explain the heterogeneity are the daily hours of phone use, social skills, and the year of study; however, these data are underreported in studies. Furthermore, worldwide, we found 26 studies from the Middle East and Asia that met the inclusion criteria, and only two studies in Europe and America.

It is recommended that future prevalence studies use random sampling, report the sample calculation, and detail the setting, specifying the major, year of study, age and sex of the participants. In addition, it is recommended that studies use the cut-off points of the NMP-Q scale to define nomophobia as absent, mild, moderate, and severe and that they present prevalence rates according to characteristics such as sex, major, and year of study. Finally, more studies are needed in other European and American countries.

Our study also has certain strengths. We conducted a comprehensive search of multiple databases and reviewed the references of included studies to capture more studies. In addition, we only included studies that used the NMP-Q scale to standardize and find studies with comparable prevalence rates. We also performed subgroup analyses to assess the heterogeneity found.

The prevalence of nomophobia in university students was very high. According to severity, the prevalence of mild, moderate, and severe nomophobia was 24%, 56%, and 17%, respectively. Regarding countries, Indonesia had the highest prevalence of severe nomophobia (71%) and Germany had the lowest (3%). The prevalence was similar according to sex and major. We recommend that further studies be conducted in more countries using the NMP-Q scale to make them comparable. We also suggest educational programs on the appropriate use of technology in university students.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Moises Huarhua, Universidad Peruana Unión, who provided language help of this article. Funding for open access charge: Universidad Peruana Union (UPeU).

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2023.29.1.40.

Figure 2

Prevalence of mild nomophobia in university students. ES: effect size, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 3

Prevalence of moderate nomophobia in university students. ES: effect size, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 4

Prevalence of severe nomophobia in university students. ES: effect size, CI: confidence interval.

Table 1

Characteristics of the included studies assessing the prevalence of nomophobia in university students (n = 28)

Table 2

Prevalence of nomophobia in university students and subgroup analysis

References

1. King AL, Valenca AM, Silva AC, Baczynski T, Carvalho MR, Nardi AE. Nomophobia: dependency on virtual environments or social phobia? Comput Hum Behav 2013 29(1):140-4.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.025

2. Leon-Mejia AC, Gutierrez-Ortega M, Serrano-Pintado I, Gonzalez-Cabrera J. A systematic review on nomophobia prevalence: surfacing results and standard guidelines for future research. PLoS One 2021 16(5):e0250509.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250509

3. Civico Ariza A, Cuevas Monzonis N, Colomo Magana E, Gabarda Mendez V. Young people and problematic use of technologies during the pandemic: a family concern. Hachetetepé 2021 (22):1-12.

https://doi.org/10.25267/Hachetetepe.2021.i22.1204

4. Darvishi M, Noori M, Nazer MR, Sheikholeslami S, Karimi E. Investigating different dimensions of nomophobia among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2019 7(4):573-8.

https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.138

5. Humood A, Altooq N, Altamimi A, Almoosawi H, Alzafiri M, Bragazzi NL, et al. The prevalence of nomophobia by population and by research tool: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Psych 2021 3(2):249-58.

https://doi.org/10.3390/psych3020019

6. Nurwahyuni E. The Impact of no mobile phone phobia (nomophobia) on mental health: a systematic review. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Nursing (ICON); 2018 May 7–10. Athens, Greece.

7. Daei A, Ashrafi-Rizi H, Soleymani MR. Nomophobia and health hazards: smartphone use and addiction among university students. Int J Prev Med 2019 10:202.

https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_184_19

8. Kim H. Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction. J Exerc Rehabil 2013 9(6):500-5.

https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.130080

9. Bhattacharya S, Bashar MA, Srivastava A, Singh A. Nomophobia: no mobile phone PhoBIA. J Family Med Prim Care 2019 8(4):1297-300.

https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_71_19

10. Gezgin DM, Cakir O, Yildirim S. The relationship between levels of nomophobia prevalence and internet addiction among high school students: the factors influencing Nomophobia. Int J Res Educ Sci 2018 4(1):215-25.

https://doi.org/10.21890/ijres.383153

11. Farooqui IA, Pore P, Gothankar J. Nomophobia: an emerging issue in medical institutions? J Ment Health 2018 27(5):438-41.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417564

12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021 372:n71.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

13. Yildirim C, Correia AP. Exploring the dimensions of nomophobia: development and validation of a self-reported questionnaire. Comput Hum Behav 2015 49:130-7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.059

14. Rodriguez-Garcia AM, Moreno-Guerrero AJ, Lopez Belmonte J. Nomophobia: an individual’s growing fear of being without a smartphone: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 17(2):580.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020580

15. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan: a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016 5(1):210.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

16. Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015 13(3):147-53.

https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054

17. Lee S, Kim M, Mendoza JS, McDonough IM. Addicted to cellphones: exploring the psychometric properties between the nomophobia questionnaire and obsessiveness in college students. Heliyon 2018 4(11):e00895.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00895

18. Matoza-Baez CM, Carballo-Ramirez MS. Nomophobia level on medical students from Paraguay, year 2015. Ciencia e investigación médico estudiantil Latinoamericana 2016;21(1):28-30.

19. Throuvala MA, Griffiths MD, Rennoldson M, Kuss DJ. Mind over matter: testing the efficacy of an online randomized controlled trial to reduce distraction from smartphone use. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 17(13):4842.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134842

Appendices

Appendix 1

List of studies included in a systematic review

A1. Davie N, Hilber T. Nomophobia: is smartphone addiction a genuine risk for mobile learning? Proceedings of the 13th International Conference Mobile Learning; 2017 Apr 10-12; Budapest, Hungary.

A2. Bartwal J, Nath B. Evaluation of nomophobia among medical students using smartphone in north India. Med J Armed Forces India 2020;76(4):451-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2019.03.001

A3. Celik Ince S. Relationship between nomophobia of nursing students and their obesity and self-esteem. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2021;57(2):753-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12610

A4. Schwaiger E, Tahir R. Nomophobia and its predictors in undergraduate students of Lahore, Pakistan. Heliyon 2020;6(9):e04837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04837

A5. Guin NB, Sharma S, Yadav S, Patel D, Khatoon S. Prevalence of nomophobia and effectiveness of planned teaching program on prevention and management of nomophobia among undergraduate students. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2020;11(9):64-9. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i9.10987

A6. Marthandappa SC, Sajjan SV, Raghavendra B. A study of prevalence and determinants of nomophobia (no mobile phobia) among medical students of Ballari: a southern district of India. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2020;11(5):575-80. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i5.9390

A7. Ismail PA, Patel D, Patel H, Patel F, Patel D. A study to assess the level of nomophobia among students at Sumandeep Nursing College, Vadodara with a view to develop an information booklet. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2020;11(3):121-4. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i3.707

A8. Chethana K, Nelliyanil M, Anil M. Prevalence of nomophobia and its association with loneliness, self happiness and self esteem among undergraduate medical students of a medical college in coastal Karnataka. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2020;11(3):523-9. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i3.1215

A9. Qutishat M, Lazarus ER, Razmy AM, Packianathan S. University students’ nomophobia prevalence, sociodemographic factors and relationship with academic performance at a University in Oman. Int J Afr Nurs Sci 2020;13:100206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100206

A10. Torpil B, Unsal E, Yildiz E, Pekcetin S. Relationship between nomophobia and occupational performance among university students. Br J Occup Ther 2021;84(7):441-5. https://doi.org/10.1177/03080226209509

A11. Iscan G, Yildirim Bas F, Ozcan Y, Ozdoganci C. Relationship between “nomophobia” and material addiction “cigarette” and factors affecting them. Int J Clin Pract 2021;75(4):e13816. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13816

A12. Ahmed S, Akter R, Pokhrel N, Samuel AJ. Prevalence of text neck syndrome and SMS thumb among smartphone users in college-going students: a cross-sectional survey study. J Public Health 2021;29(2):411-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01139-4

A13. Jilisha G, Venkatachalam J, Menon V, Olickal JJ. Nomophobia: a mixed-methods study on prevalence, associated factors, and perception among college students in Puducherry, India. Indian J Psychol Med 2019;41(6):541-8. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_130_19

A14. Cain J, Malcom DR. An assessment of pharmacy students’ psychological attachment to smartphones at two colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ 2019;83(7):7136. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7136

A15. Apak E, Yaman OM. The prevalence of nomophobia among university students and nomophobia's relationship with social phobia: the case of Bingol University. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions 2019;6(3):609-29. https://doi.org/10.15805/addicta.2019.6.3.0078

A16. Al-Balhan EM, Khabbache H, Watfa A, Re TS, Zerbetto R, Bragazzi NL. Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of the nomophobia questionnaire: confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis: implications from a pilot study in Kuwait among university students. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2018;11:471-82. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S169918

A17. Ayar D, Ozalp Gerceker G, Ozdemir EZ, Bektas M. The effect of problematic internet use, social appearance anxiety, and social media use on nursing students’ nomophobia levels. Comput Inform Nurs 2018;36(12):589-95. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000458

A18. Alahmari MS, Alfaifi AA, Alyami AH, Alshehri SM, Alqahtani MS, Alkhashrami SS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of nomophobia among undergraduate students of Health Sciences Colleges at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Res Prof 2018;4(1);429-32. https://doi.org/10.21276/ijmrp.2018.4.1.088

A19. Sethia S, Melwani V, Melwani S, Priya A, Gupta M, Khan A. A study to assess the degree of nomophobia among the undergraduate students of a medical college in Bhopal. Int J Community Med Public Health 2018;5(6):2442-5. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20182174

A20. Harish BR, Bharath J. Prevalence of nomophobia among the undergraduate medical students of Mandya Institute of Medical Sciences, Mandya. Int J Community Med Public Health 2018;5(12):5455-9. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20184833

A21. Dasgupta P, Bhattacherjee S, Dasgupta S, Roy JK, Mukherjee A, Biswas R. Nomophobic behaviors among smartphone using medical and engineering students in two colleges of West Bengal. Indian J Public Health 2017;61(3):199-204. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_81_16

A22. Akun A, Andreani W. Powerfully tecnologized, powerlessly connected: the psychosemiotics of nomophobia. Proceedings of 2017 10th International Conference on Human System Interactions (HSI); 2017 Jul 17–19; Ulsan, South Korea. p. 306-10. https://doi.org/10.1109/HSI.2017.8005051

A23. Chandak P, Dagdiay M. An exploratory study of nomophobia in post-graduate residents of a teaching hospital in Central India. Presented at the 19th WPA World Congress of Psychiatry; 2019 Aug 21–24; Lisbon, Portugal. https://doi.org/10.26226/morressier.5d1a036c57558b317a13fd71

A24. Madhusudan M, Sudarshan BP, Sanjay TV, Gopi A, Fernandes SD. Nomophobia and determinants among the students of a medical college in Kerala. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2017;6(6):1046-9. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijmsph.2017.0203115022017

A25. Kanmani A, Bhavani U, Maragatham RS. Nomophobia: an insight into its psychological aspects in India. Int J Indian Psychol 2017;4(2):5-15. https://doi.org/10.25215/0402.041

A26. Yildirim C, Sumuer E, Adnan M, Yildirim S. A growing fear: prevalence of nomophobia among Turkish college students. Inf Dev 2016;32(5):1322-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666915599025

A27. Farooqui IA, Pore P, Gothankar J. Nomophobia: an emerging issue in medical institutions? J Ment Health 2018;27(5):438-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417564

A28. Veerapu N, Philip RK, Vasireddy H, Gurrala S, Kanna ST. A study on nomophobia and its correlation with sleeping difficulty and anxiety among medical students in a medical college, Telangana. Int J Community Med Public Health 2019;6(5):2074-6. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20191821

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles in Healthc Inform Res

-

Effect of Mobile Health on Obese Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis2019 January;25(1)